Level Design 101 - Little Medusa

Everyone hates the water level. It's just one of those tropes that crop up time and time again in video games. Weather from oxygen limits or poor swimming ability, water levels are synonymous with broken controllers and rage quits.

However, this trope highlights one of the core mechanics designers can use when creating a game, namely the stages, environments, or levels that characters find themselves in. More than just an array of platforms to move around on, levels can add to a game's narrative, provide their own unique challenges, and make players feel strong and accomplished.

The following are some elements to be considered when designing levels. We used Little Medusa as a guide and example, since, as an action-puzzle game, the levels are integral to the game's mechanics and appeal.

Emotional Response

Fun is only one reason to play a video game, and every game has something to offer its players. Some fulfill the drive to be or feel powerful, by providing satisfying characters with awesome abilities or mechanics for leveling up and growing stronger. Other games seek to elicit a sense of mastery for the player, entering into a state of flow where they are performing at their peak. Still, other titles are meant as humorous escapes, full of colorful characters or dialogue.

There are many ways to create these sentiments and feelings in the player, such as characterization, feedback mechanics, and, of course, level design. Levels can be created to evoke a range of emotions in the player. Consider the way lighting in Bioshock increases tension or the placement of the challenging disappearing blocks in Mega Man that feel soooo good when you get past them.

With Little Medusa, while much of the art is charming, the levels themselves are meant to challenge the player and to confer a sense of mastery. The levels are designed around puzzles and the primary mechanics of moving petrified enemies around. Using a handful of elements in interesting combinations, some truly devilish levels can be created to put the player's skills to the test.

Gameflow

The other half of the equation, mastery, is achieved through the flow of the game. When players figure out how a mechanic or new enemy works, and how to exploit them, they feel good. This is done first by presenting new mechanics in relatively safe, simple environments, and then ramping up the difficulty in later stages while still using these same mechanics.

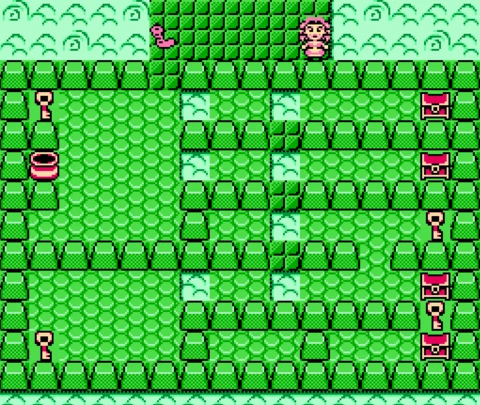

For example, the first image is Fire-1, where we introduce Little Medusa's Blindfolded enemies, who can push other petrified enemies. In the second, we have Fire-6, which uses these enemies and other mechanics the player has encountered (like arrow tiles and Cerberus heads) to make the difficulty greater, and the level more satisfying to beat.

As with all game mechanics, level design can be married to other systems or features to produce the same effect. For example, continuing the theme of the challenge, Little Medusa has a trophy system, which awards players with a trophy when they can beat a level in a certain time limit. This provides an extension of the sense of challenge and mastery that the level design offers - not only do players need to figure out a puzzle but now they are rewarded if they can solve it quickly.

Limitations

Another important aspect to consider when designing levels is limitations. These can be restrictions you face from the hardware you are developing on (like the limitations of the NES in the case of Little Medusa) or self-imposed restrictions bases around the genre or abilities of the character.

Let's start with the former. Working with retro platforms can actually make designers and artists better because the restrictions force them to be creative. For example, observant players may notice that in Little Medusa, there is only ever one type of "major enemy" in a level at once. That's because the graphical restrictions prevent us from loading several different types of enemies at once, based on the "banks" these enemies share in the game's memory.

Take Wind-6 above. How much harder would this level be with Centaur enemies (which can shoot arrows) rather than the just snakes? With the mobile and deadly archers along with the dashing serpents, the difficulty would be taken to new extremes.

However, we are prevented from having snakes and centaurs at the same level. Since we can't have multiple enemy types, we decided to leverage the design of the level.

What we did here is replaced the snakes from centaurs, and added more of them in challenging locations. Now, when you complete a path by filling in one of the pits, you essentially create a bridge that unleashes one of these deadly enemies. This Little Medusa level is a perfect example of retro console restrictions forcing our designers to be more creative and strategic.

As mentioned, the other type of limitation is those that are self-imposed. A designer might put restrictions on how the level is designed to provoke certain feelings in a player. For example, in Star Wars Jedi Knight: Jedi Academy, there is a level that robs the player of their lightsaber, which they have had access to for the entire game.

This is a shocking twist that forces players to use their other weapons and Force abilities to successfully complete the level. In compensation, the level does not feature an abundance of lightsaber-wielding enemies, which typically can only be defeated by swordplay. It's unique, it's challenging, and it's memorable - and it was accomplished through limitations.

Narrative

Another element to level design is narrative. Designers should use every element at their disposal, not just text and dialogue, to complement and enhance a game's narrative. This can be as simple as levels becoming harder to mirror and resonate with the hero's quest to become more difficult.

With Little Medusa, the progression of the levels coincides with Artemiza's realization that her cleverness and cunning are more of an asset than her appearance. At the beginning of the game, Arte is arrogant and haughty. Through her journey as a gorgon, she becomes more and more ingenious at navigating the levels, and her personality develops and matures in tandem.

Player Choice

Providing players with choices can also help when designing levels. Branching paths, multiple ways to approach situations, and varied win conditions - these aspects are right at home in a game from the Hitman or Dishonored franchises.

However, these can be accomplished even on the good old NES. Little Medusa accomplishes this through optional bonus objects.

Take Aether-3 for example. The Arte head (a 1-UP, of course) in the upper right is not mandatory to complete the stage. Getting it, however, provides several bonuses - another life, a huge point boost, and the chance to meet the score minimum to get the trophy for this stage. Acquiring the Arte head is quite the task, however. Players must navigate a cyclops enemy past the flames of two constantly rotating Cerberus heads, all while dodging the steady gait of the cyclops on tight, confined paths. It's difficult, it's worth it, and it's optional.

Conclusion

Level design is just one more trick designers can use to make their games fun, interesting, and exciting. It's another tool in the toolbox, another arrow in the quiver, another snake on the Medusa head. Even on a retro console like the NES or a retro game like Little Medusa, the level design offers powerful opportunities if designers consider a few elements before jumping in.

Thanks for reading, and check out Little Medusa if you enjoy brain-boggling puzzle action.